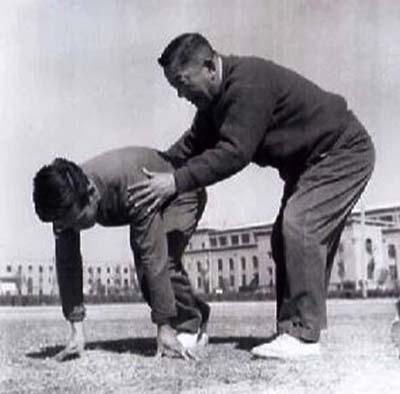

This is not China’s 110 meter hurdler Liu Xiang (刘翔), an Olympic gold medalist and World Champion, but Liu Changchun (刘长春), China’s first Olympian, 74 years older than Xiu Xiang.

China’s First Olympian

Liu Changchun was born in 1909, two years before the Manchu Emperor was thrown out. However when he grew up, he once again lived under Manchu rule that was militarily backed by Japanese force in China’s northeast.

His father was a shoemaker but they were so poor that the old Liu couldn’t afford to provide shoes to his own children so young Liu was running bearfoot all the time, even in freezing winters, except during Chinese New Year’s festival seasons.

When he was 10, Liu Changchun was sent to a school that was 5 kms away from home. In the next few years, he had to run 10 kms between school and home on every school day.

All these somehow prepared him to become a great sprinter.

In 1929 when he turned 20, he broke the national records in men’s 100m (10.8s), 200m (22.4s) and 400m (52.4s). By then the record of the gold medalist for men’s 100m in Amsterdam Olympics 1928 was also 10.8s.

Three years later in 1932, Liu Changchun decided to represent China to participate the 10th Olympics in Los Angeles, the USA. Japanese occupiers wanted him to represent Manchu state (Manchukuo) instead. He refused, thus he was placed under Manchu police surveillance and prohibited to leave China’s northeast region.

One night, when his friend visited him, they swapped the clothes, which allowed Liu Changchun to flee to Shanghai.

When Japanese and Manchus learned what happened, they published a news on the paper, claiming that Liu was about to attend the 20the Olympics on the behalf of Manchu State.

The news spread fast, and Liu was condemned by Chinese public for working with Japanese and Manchus, for which he was labeled traitor.

Liu Changchun had to post statements on Beijing and Tianjin Newspepters, declaring that “I am a Chinese, the descendent of Yellow and Red Emperors, there is no way I will represent Manchu state in the 10th Olympics (我是中国人,我是中华民族炎黄子孙,我绝不代表伪满州国出席第10届奥林匹克运动会),” and “I have my conscience, I have my hot blood, as a decent Chinese I will never betray my heritage and work for Manchus (苟余之良心尚在,热血尚流,又岂忘掉祖国,而为傀儡伪国作马牛).”

Despite the misunderstanding was cleaned up, the drama did have stressed him tremendously.

By then it was only one month away from the opening ceremony of the 10th Olympics. He just got enough time to secure a ticket to board a ship from Shanghai, and arrived in Los Angeles after 25 days on the sea on August 2, 1932.

The long period of ocean travel further took its toll, which seriously affected Liu Changchun’s physical strength and performance. He failed to be qualified for final.

But the one-man team has made the history. It raised Chinese nation’s flag in the Olympics stadium for the first time.

The Chinese government under KMT’s administration, however, was too corrupted and too weak to offer a basic support for its athlete. After the games, Liu Changchun had no money to return to China and relied on the donations from the local Chinese community to get a ticket.

His leg was also injured. He was soon forced to retire from the profession of track and field and there were years he was unemployed.

Unfulfilled Dreams

After 1949, he worked as a professor in a university in Dalian for over 30 years, training young athletes until his retirement in the end of the 60s.

In 1982, Liu Changchun was in his advanced age of 73 and his health was fading. His son noticed the old man developed a new habit: the veteran sprinter would keep staring outside through windows while repeating the names of two cities – Shanghai and Los Angeles.

The son understood that in the next year 1983, a National Games would be hosted by Shanghai, and two years later in 1984, PRC would send the first team to attend the 23th Olympics taken place, again, in Los Angeles.

Half a century ago, Liu Changchun overcame all odds to travel from Shanghai to Los Angeles to represent China in Olympics for the first time in history.

“Considering my health, do you reckon I would still have a chance to go to Shanghai and Los Angeles?” he asked his son.

However, just two months before the National Games commenced in Shanghai in May, Liu Changchun fell in grave ill and died.

He left his unfulfilled dream of revisiting Shanghai and Los Angeles.

Also left behind is his book Game of Sprinter (短跑运动), which becomes the classic in Chinese sprinter training.

Dreams Actually Fulfilled?

Four months after Liu Changchun’s death, Liu Xiang was born in Shanghai.

Liu Xiang, the man looks so much like Liu Changchuan, went on to become the first Chinese to win Olympic gold medal and World Championship on men’s track and field events, while Los Angeles is the city Liu Xiang visited and revisited frequently.

I haven’t implicated anything here regarding a link between Liu Changchun and Liu Xiang. But I would like to suggest that incarnation could occur during any stage of pregnancy, even days, months and years after birth.

A final note, speaking Los Angeles, it has always been a city of significance for Chinese athletes. In 1984 on the 23th Los Angeles Olympics, that Liu Changchun wished he could attend at the final stage of his life, Chinese pistol shooter Xu Haifeng (许海峰), who was specialised in the 50 metre pistol, became the first person to win a gold medal for China in the Olympic Games.

Have Liu Changchun’s dreams actually been fulfilled, after all?